After making it through the initial application selection and conquering a first set of introductory interviews the interview process often moves on to some form of “technical challenges”. The goal here is to check your skills on a practical task in the area you will be working in. Oftentimes they are used to sort out people that can just talk “nicely” about doing things vs. actually doing them. The challenges will often be a basis for further conversation. Challenges can take many forms, and so this post will first give some general tips and then dive into the different forms they can take and what to look out for.

The focus of this post will be engineering, as that’s what I know best, but a lot of the general tips should be generally applicable. We’ll first look at a good mindset and some general tips. Then we move on to different challenge setups – namely, is it take-home challenge or a live challenge. To round things out we’ll examine different challenge topics: Coding, Pull Request Review, Architecture & People Manager.

Who am I to speak on challenges in interviews? I’ve done quite a few of them myself and also was the one grading them on many (> 100) occasions as well as teaching people how to grade them. Thanks to my friend Sara Regan for proofreading and providing suggestions.

As a small disclaimer, of course these tips are biased towards how I grade challenges and how it has been done at companies I work at. There are probably people out there who are not interested in you deliberating options and just want you to quietly solve a challenge. If they exist, I’d say they are by far the minority. That said, of course people can also have valid different opinions and approaches to this. Grain of salt applied.

This part of a blog post series I’m writing covering:

- CV, cover letter & screening interview

- Technical challenges ←you are here

- Interviews

Let’s get into it!

Mindset

The most important thing that I think most people get wrong about technical challenges: It’s less about IF you can solve it, but about HOW you solve it.

Many times I’ve seen someone seemingly half-ass a challenge as they regarded it just as a small hoop to jump through to get to the “real” interviews. This is often exacerbated by the problems given out to be perceived as “toy problems” that are easily solved. This was perhaps most showcased in an interview where the candidate was refusing to implement FizzBuzz instead showing an online solution that worked with a precisely initialized randomness generator. Solving it is not the point.

Most challenges will include something akin to “treat it as if it was real production code you wanted to work on with a team” or something to that tune. I can only implore you to take them seriously. In many cases, whoever is reviewing the challenge doesn’t know you or your background and they can’t assume you know something. Put yourself in their shoes: they want to hire someone and can only assume that during the hiring process you’re trying to show your best self. Even if they don’t assume that, they might see other people who are more diligent and will be more likely to give them the job. Fair or not, this is what they have to go by to see if you’re a fit for the company and also at what level they think you can work at.

You may also be surprised by the statement that they don’t know you, after all this is already after a couple of rounds of interviews – they must know you, right?! Well, it depends on the company but many companies try to remove biases from the process as much as they can. That means that especially people who grade take home challenges or do an in person technical challenge with you often haven’t seen your CV nor have they been in a previous interview. Their task is to judge your proficiency solely based on the challenge. And so, give it your best to leave the best impression. This is not the case everywhere, especially small companies can’t afford to do this. However, it’s still relatively common these days as far as I’m aware.

General Tips

Let’s start it off with some quickfire tips for all challenges – coding, people manager, case study – before we go into more detail:

- Take the challenge seriously (yes, I’m a broken record on this), this is an interview situation – it’s fair to assume that they expect you to bring your best and you really should. Aim to deliver high quality and if in doubt mention what you’d do normally and say why you don’t right now or ask the interviewers if you should.

- Communicate your thoughts and decisions! As I said, it’s about how you solve a problem, people can’t peek into your thoughts so make them accessible to them.

- Record questions you asked yourself

- Communicate decisions you have made along alternatives you considered and their tradeoffs

- If you don’t know how something is meant, ask the interviewers esp. about ambiguity. I have seen many challenges where ambiguity in the challenge description was part of the challenge design to see how you deal with ambiguity and how you try to clarify it. Asking questions about the problem or even how far the solution should go usually nets you bonus points. Especially if you are unsure about a question or requirement make sure to clarify your understanding to avoid going off in the wrong direction as much as possible

- Go through company values and the job posting again before solving any of the challenges. They give you an idea of what to focus on. If “documentation” is one of the company values and you provide none, that doesn’t spell well for you. If a major part of your future job is solving database performance problems, you should make sure your schema and query design in a coding challenge are immaculate.

- Nobody expects you to be perfect, a mistake or even a couple mistakes don’t disqualify you. Keep going.

- Sadly, not all challenges, interviewers and reviewers are good. Some of them are pretty bad actually, due to a host of reasons (sometimes unqualified engineers are thrown into the mix of interviewing). Try to follow the tips to make the best out of the situation, but I’ve even heard of interviewers refusing to engage in questions about the task. Always remember that interviewing is a two way filtering process – it’s fine for you to decide that you don’t want to work for this company. I have once aborted an interview process because I was sure that what they filtered for with the interviews as I experienced them was not a culture I’d like to work in.

Challenge Setup

Generally speaking, there are 2 types of challenge setups – you can take the challenge home and solve it on your own time or you may need to solve it live on the premises (“in person”). Both challenge setups have their peculiarities, so let’s take a look at them.

Take-Home Challenges

Usually you get sent the challenge and then have a week or 2 to solve them. They usually also fall into 2 categories (or a mix), challenges that are just graded by someone or challenges that you bring with you to the next interview to discuss them with someone.

Here’s what to look out for specifically (while the general tips still apply of course):

- Sadly, most of the challenges will take more time to solve them than advertised. I don’t know why this is, but I usually think that someone comes up with an idea that tests as many things they deem important and then pack them all into the challenge. They then make the typical “guesstimate” how long they take to solve and are off by the usual factor of 2-3x. If it takes longer than you’re willing to invest, make sure to communicate it in the challenge or better even ask your contact person. As in: “I don’t think I can finish the challenge due to time constraints, can I get more time please or alternatively could you please tell me if I should rather focus on finishing all the requirements or on writing tests?”

- Taking into account the above, make sure that you have enough time during the allotted time frame to solve the task without depriving yourself of sleep. Also be careful not to splatter your schedule with too many coding challenges at once.

- Especially with take-home challenges document your major decisions, as you may not be there for the reviewer to ask questions. Be proactive about this. For coding challenges I’d feature a section in the

READMEabout decisions taken and then also reference it from relevant parts of the code via comments – make it impossible for the reviewer to miss. They’re also human and make mistakes after all. - If you think something would be too much to include right now or you can’t fit it in due to time constraints, again document it. A common case in a coding challenge would be “normally I’d put this in a background job queue, but due to time constraints I’ve decided to leave it inline for now”.

- Review your entire challenge before submission with the mind of a reviewer. Read the challenge description again and make sure you covered all the points.

- If the take-home challenge is the subject of a later interview, make sure to re-review your own challenge before the interview. Sometimes a month or more can pass between you completing the challenge and the interview – you should be intimately familiar with it.

Live Challenges

These are challenges where you are presented with the challenge in an interview setting while the interviewers are present. Sometimes you are given a short time (~30 minutes) by yourself to study and prepare, sometimes everything is done on the spot. This is often an extremely stressful situation, but if your interviewers are any good they’re aware of that and will try to make it as comfortable as possible for you.

These tips are also applicable if you first solved a take-home challenge but are then discussing it in a later interview.

- Ask clarifying questions! About the problem in the challenge, about how you are expected to solve it and about what you can do (“Can I google?” – answer should usually be yes). This gives you the benefit that you know exactly what you should be doing, but also gives you some time to already think about the challenge and calm down.

- Restating the core of the challenge in your own words is a great way to absolutely positively make sure that you’re on the same page as the interviewers about what the task is. For challenges, I like to keep my own bullet points on what is required – for instance at the top of the file for a coding challenge.

- Come well prepared. A live challenge should never be sprung on you out of the blue. For a coding challenge make sure that you have your programming environment completely set up as you need it and confirmed working. At best, create a small sample project before at home with all the basics setup working. You don’t want to start installing Ruby & VS Code during your interview.

- Also, be aware that if done on your personal laptop (no matter if remote or locally) people will likely see your desktop so make sure it’s presentable

- Turn off notifications/communication programs in advance so that you don’t get distracted and so that your interviewers don’t see something they shouldn’t see

- Everybody understands that it’s a stressful situation, take some time to think through the problem, you don’t need to be talking all the time.

- However, still remember to communicate major questions you are thinking about or decisions you are considering right now. This helps your interviewers, and they might even help you. For instance, I’d always help people if they were searching for a specific method or how to set up their test environment. The interview shouldn’t be about testing easily google-able knowledge, however sadly some may be.

- Some of these will be labeled as “pairing” challenges, 99% of the time it won’t be actual pairing. While the interviewers may help you and discuss problems with you, they usually won’t give you critical solutions or take to coding themselves. I feel the need to mention this, as I always feel that this “pairing” label is deceptive. However, if they do give you suggestions, consider them and elaborate on them.

- Sometimes the challenge isn’t even designed to be doable in the allotted time or there is a base version with multiple “extension points” in case there is time left. A good interviewer will tell you this. If unsure, ask. I have passed coding challenges in the past with flying colors although I didn’t finish it.

Challenge Topic

There are many different main topics for challenges throughout different companies and seniority levels – the most common of which is certainly the coding challenge for developers. They often have their own specifics to go with them no matter if they are take-home or live, so let’s dive into them!

Coding Challenge

They are usually part of an engineering hiring process in one form or another. A “trial” day is also a coding challenge in big parts, as in you’re given a problem and are asked to solve it with the people around.

Whether or not coding challenges are good is not the topic of this blog post. I know many programmers hate them with a passion. I can only tell you that I’ve seen candidates with 5+ years of experience that couldn’t explain what a `return` statement does. Especially if you have a lot of open source code it’s common to wish that they’d just review that instead. And that makes sense and some companies do it. However, a challenge comes with the pro that it’s normally standardized across the company, can be the basis of discussion in further interviews and it hopefully probes for skills relevant to the job. For instance, you can say people could just look at benchee when interviewing me, but it would tell you nothing about how I work with databases or web frameworks.

Why am I telling you this? I’ve seen more than a couple of candidates who let their disdain for any type of coding challenge show while they’re solving it or discussing it. That’s not in your best interest – if you take on this step, even if you hate it, handle it professionally.

- One more time: Take it seriously! Show your best work!

- I mentioned before that challenges often contain a phrase like “production quality” but what does that mean? Here is a small list:

- Naturally the application fulfills the task as described

- Tested appropriately – in some places missing tests are an auto reject, also make sure the tests actually pass

- The application should not emit warnings

- Reasonably readable code

- No leftovers like TODO comments or out commented code

- A README that describes what the application is about and how to set it up

- Document the versions of all major technologies you have used (Elixir/Erlang/Postgres version)

- It usually does not mean that the application should actually be deployed, although it may earn you bonus points

- Similarly, you don’t need to have a CI running unless you want it for your own safety (the amount of challenges I’ve seen that were broken on some ‘last minute refactoring’ is staggering)

- Remember that it is more about how you solve it versus if you solve it. You can give an impression of overengineering or underengineering all too easily.

- A classic thing I often see is people completely forgetting about any form of separation of concerns, and just mixing as much as possible into a single module as “the challenge is so small”. This is usually not in your best interest, as you want to show how you’d work on a “real” project. Also, it usually makes for overly complicated tests.

- On the other end of the spectrum I see people basically making up future requirements that are in no way hinted at in the challenge and so they make their code overly complex and configurable, sacrificing readability.

- Both of the above are bad, best document why you did or didn’t do something and say what you could have done differently.

- While using linters & formatters is usually not a requirement, they help you catch errors and make it nicer to read for your reviewers. I especially recommend using these if you’re rusty.

- It should go without saying, but follow best practices as you know them: Add indexes where appropriate. Don’t use float columns to store money values.

- Communicate decisions! For instance, you may have decided not to add an index for a column that is queried because the query is fast enough without it and the application is write-heavy and so the index may do more harm than good. Without documenting this, the reviewer will never know and might just assume you don’t know how to use indexes.

- Be mindful that some reviewers will read your git history, avoid cussing out the challenge or company. (yes, this point is here for a reason)

- If you use unusual patterns, make sure to explain what they are and why you are using them (and ask yourself if it’s really necessary).

- On take-home challenges: Make extra sure to use readable names and add a bit more documentation than you usually would, these are people that don’t know you and can’t ask you. Make the reviewers job as easy as possible.

- Especially for take home challenges I’m paranoid that it won’t work on the machine of the reviewer. So, right before submitting I’ll clone the entire repo freshly into a new directory and follow my own setup guide to see that everything works and I didn’t forget to check in a file or forgot a setup step.

Let me expand on “document things” a bit more. I remember a peculiar coding challenge where its design was problematic as it sent all requests through a single central GenSever essentially bottle-necking the entire application. I wrote a whole paragraph on why I think this is a bad design, but still implemented it as the task description specifically asked for it. I then went into how I would implement it differently and what I also did in the current challenge to lessen the negative impact of this architecture.

Some coding challenges you will encounter aren’t truly coding challenges but puzzles. I’ve seen coding challenges that just directed you to an URL and from there you need to figure out the format, get links to CSV files, a text file and then try to figure out what your task is. I can just say that I think these are terrible, try your best to solve them, but also think about what kind of skills the company may be valuing if they choose to test engineers like that.

Lastly the aforementioned FizzBuzz is a well known challenge and well suited to demonstrate what I mean by “taking it seriously” as well as showing how complex a “toy” problem can get. So, I wrote an entire blog post about it and its different evolutionary stages. If you want to dive more into coding challenges, that’s a good next spot to check out.

Pull Request Review

It feels like in recent years “pull request reviews” have become more common as a form of challenge. The premise is simple: You are to review a pull request. Sometimes it’s adding a feature, sometimes it’s building out an entire new application. However, the pull request will always be intentionally bad, so that you have something to fix.

What I like about this kind of challenge is that it’s less likely to go vastly over time while also checking communication skills. So, what should you look out for in particular here:

- Again, pretend it’s real. Pretend you’re reviewing a real pull request from a real human being. Be kind, be helpful. One of the easiest ways to fail these is by being an ass.

- Proper Pull Request Reviews are a topic of their own (see for instance this post by Chelsea Troy) but in short things that can help:

- Also praise good code, don’t focus on just the negatives

- Ask questions if you are not sure why something is the way it is

- Provide suggestions on how to change things, if you recommend to use a particular method best provide a link to its documentation

- Make sure to mention why you think something needs changing; “this is bad” comments help no one

- Summarize your main points in a final summarizing comment, perhaps offering to also pair on it

- Check if the PR actually solves everything that is mentioned in the issue it is trying to solve

- Check for readability

- Make sure everything is appropriately tested

- Be very diligent, many of these challenges also sneak in some form of insecure code the kind of which you hopefully don’t see too often. Don’t overlook something because “they probably know what they’re doing” – it’s a challenge, they likely don’t.

- See if tests & linters pass, if there is no CI try to run it yourself. It’s generally best to check out the code yourself to be able to play with it anyhow.

Architecture/Design Challenge

This is a type of challenge you typically only face at the level of Senior or above, sometimes it’s also called a “Design interview”. Essentially you’ll be given a scenario for an application and asked to design an application that solves this scenario. Sometimes the scope of this is choosing the entire tech stack and general approach, sometimes the focus is solely on the database design – although the latter will come up in both cases. You will not implement it in code, but you will talk through it and probably draw some diagrams.

- Ask about the requirements for the application, chances are that there are things that aren’t completely spelled out but could have an impact. At the very least, you can make sure to arrive at a common domain terminology. Some questions that might make sense to ask for a web application:

- Who uses the application? What for?

- Will there only be a browser client for this or do we have other possible clients as well?

- What kind of traffic can we expect? Will it be spiky?

- What is the expected response/processing time?

- How much data will we need to store approximately?

- Are all users of the system the same or do we have different roles?

- What’s most important to the system: Should it always be correct, always be fast or always be available?

- … and of course many more, system design is a WIDE topic …

- Especially here: make the options you’re weighing known. This interview is all about decisions you make and tradeoffs you consider. Whenever you bring something up, an interesting discussion with the interviewers might ensue. I once deliberated whether we could use Sidekiq in a scenario where we absolutely can’t lose jobs, as I was aware of a related problem in the base version of Sidekiq. This open deliberation seemingly impressed my interviewers, had I kept it to myself they would have never known.

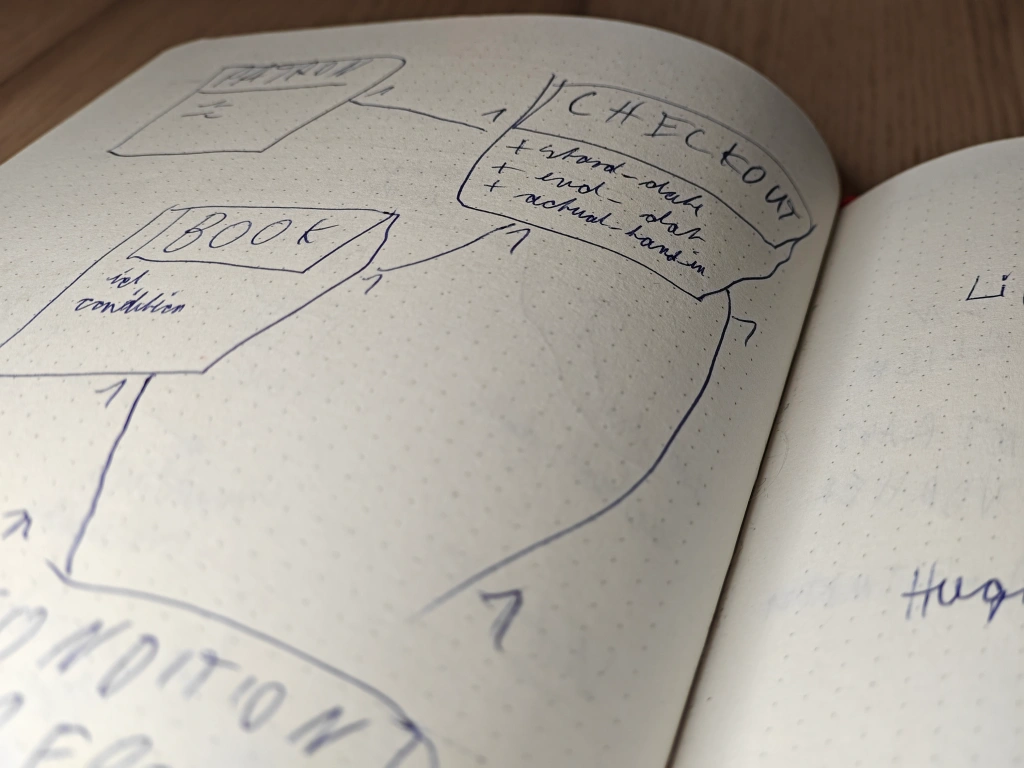

- Be visual, draw diagrams of the application, its major components and its environment as well as the database design. All of that is the basis for the discussion and can help you spot inconsistencies. At best the interviewers provide you with a diagramming tools/whiteboard, but even if they don’t a piece of paper and a pen work just as well. The last time I did this I noticed that I had a dangling 1-to-1 that was related to only one table and basically only featured one meaningful column. While it seemed to make sense, I discussed the issue with the interviewers and we decided to “inline” that table again.

- Take your time to review your own design and discuss it, that way you can bring more options to the table and fix it up – all that before the interviewers get to ask their first question.

- Deliberate the pros and cons of your choices and make sure they fit the scenario. You may love microservices, but if you’re designing a system for a small 3 person business that is used a hundred times a day for the foreseeable future it’s probably not the best decision.

- Be upfront that you might not know something as well. For instance, you might figure out that for what you’re going to build some form of message queues may be a good fit, but you haven’t worked with them a lot. This tip may be controversial, however pretending to know something that you don’t is one of the easiest ways to fail interviews. If the interviewers are good and aware you’re not as familiar with the technology, they might proactively help you out or appreciate the thought but encourage you to go with a technology you’re more familiar with.

People Manager Challenge

Many companies will have specialized people manager challenges for Team Leads/Engineering Managers and up. These can come in many different forms, most of them will put you in some sort of contrived scenario with a problem and then ask you how you would go about solving that problem. More often than not, the scenario will include some form of conflict involving your reports. The form that these take varies wildly:

- You might get a conflict scenario and simply be asked what you think is happening and how you’d address it.

- You may get posts on an internal “help” forum and be asked to answer them.

- You may also be given a scenario of a team that is underperforming and be asked to help them as their new manager.

This challenge type is very different from the others and arguably more complex: You’re dealing with humans and organizational structures here. And worst of all, they are not real and context is only established via a 1-2 page briefing. There is no code you can look at and fiddle with. As a result of this, be extremely careful how you approach and answer these. You simply can not know many things for certain, make it clear that what you are noting are deliberations and ideas. Still, look at all the people in the scenario and try to figure out what is happening. What misunderstandings could there be? Are there biases at play? How can you figure it out? The solution almost always includes talking to all involved participants to get their sides of the story.

As in real life, the scenario as described is subjective. Don’t take all information and statements contained in the task description as the absolute truth. For instance, a team may be described as “underperforming” – it would be important to establish how that was determined and what it means. Maybe the team is working on a major project people are unaware of. Maybe they’re the ones actually keeping the money making legacy application alive and are hence not contributing as much to the new shiny thing (™).

In whatever way you discuss the challenge – be it talking to interviewers about the task or notes you hand in to them – make sure that your thoughts are easy to follow. Be deliberate to distinguish your levels of certainty about different aspects. Make sure you don’t just write down “Talk to Sara” but why you want to talk to her, what piece of the puzzle you want to understand there.

Closing up

And that’s another whopper about interviewing in the books. It’s a complex topic and I truly wish to expand even more on some aspects – but I won’t do it right now so that it stays half-way readable and my time invested stays… not too outrageous.

Try to show your best self, take the tasks seriously and treat them as if they were real as much as possible. Make people aware of the tradeoffs you’re deliberating and why you’re taking certain decisions. It’s not just about solving the task, but about how you solve it – and for the interviewers to understand that you have got to make it obvious to them. Don’t be afraid to discuss the challenge itself with them.

Remember as always, interviewing is not a perfect science. You can fail these challenges for all kinds of reasons – and quite some of them have nothing to do with your ability to do the actual job. If you know you struggle with “Live” challenges, try to get some practice in. Be it mock interviews with friends or applying at another company that isn’t as important to you first.

You got this!